Genetics

For a review of the genetics of FTD read this paper by Caroline Greaves from our team.

We have also published a large international study of genetic FTD in Lancet Neurology in which we looked at different aspects of age at onset and duration of disease.

We continually review the literature in order to keep an updated list of mutations in FTD-related genes. Click on the links to review a list of progranulin mutations and of tau mutations. We have also started to create lists for the rarer genetic causes of FTD, including TBK1 mutations.

FTD is neither a purely genetic illness like Huntington’s disease nor a mainly non-genetic (or sporadic) disease like Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, it sits somewhere between the two.

The heritability of FTD has been the subject of a number of studies which have revealed a complex picture:

- Heritability varies by clinical syndrome:

- If you have bvFTD, the risk of your illness being genetic is around 40-45%.

- The next most genetic form is FTD-MND, with a 20-40% risk of it being familial.

- NfvPPA is genetic in around 5-10% of people with probably a similar risk in people with a mixed or non-specified form of PPA.

- CBS is genetic in around 5% of people.

- Other disorders in the FTD spectrum (PSP, svPPA, lvPPA) are genetic in less than 1% of people.

- Heritability varies by family history:

- If you have FTD and you have 2 other first-degree relatives with dementia or one first-degree relative with a young onset dementia (i.e. starting below 65) then the risk that your form of FTD is genetic is 25-30%

- If you have no family history of FTD the risk of it being genetic is <10% (but importantly it is not zero).

For the majority of forms of genetic FTD, the disease is passed down in what is called an ‘autosomal dominant’ manner. This means that first-degree relatives of people with genetic FTD have a 50:50 or 1 in 2 chance of also carrying the genetic mutation. If people do carry the mutation then they are very likely to develop symptoms of one of the FTD clinical syndromes at some point during life.

Most genetic FTD is caused by mutations in one of three genes:

- progranulin (GRN)

- microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT)

- chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72)

Each of these three genetic groups causes between ~5-10% of all FTD, although overall C9orf72 seems to be the most common worldwide cause of genetic FTD, followed by GRN and then MAPT.

There is some variability across the world in how common each of the individual genetic groups are. For example, GRN mutations are more common in Northern Italy and the Basque country whilst C9orf72 mutations are particularly common in Nordic countries.

For GRN and MAPT there are multiple different mutations in each gene that can occur – so far we recognise more than 170 in GRN and more than 70 in MAPT.

For C9orf72, part of the gene is longer than usual – this is called an expansion. In C9orf72 there is an expansion of 6 parts of the genetic code (a hexanucleotide expansion). In people without FTD, this part of the gene is repeated less than 20 times, but in people with C9orf72-associated FTD it can be repeated hundreds or thousands of times.

Although less common than the main three genes, there are a number of other genes in which mutations have been found to cause FTD:

- TBK1

- TARDBP

- VCP

- CHMP2B

- SQSTM1

- FUS

- UBQLN2

There are also a group of other genes which may be associated with FTD but the research evidence is less clear:

- CHCHD10

- OPTN

- CCNF

- TIA1

- CYLD

Genetic testing in FTD clinics around the world will commonly screen for mutations in many of these genes at the same time. It is important to recognise that performing these screens can lead to the discovery of genetic variants that may not be relevant to that specific person’s form of FTD – some of these may be normal variations in our genetic code that do not directly cause FTD. A good example of this is the finding of ‘missense’ variants in the GRN gene, the majority of which do not seem to directly cause FTD.

At present there is no website with a definitive list of which genes are associated with FTD. There is one for ALS which is very helpful in looking at whether a specific gene has been associated with ALS or not: ALS online Database (ALSoD).

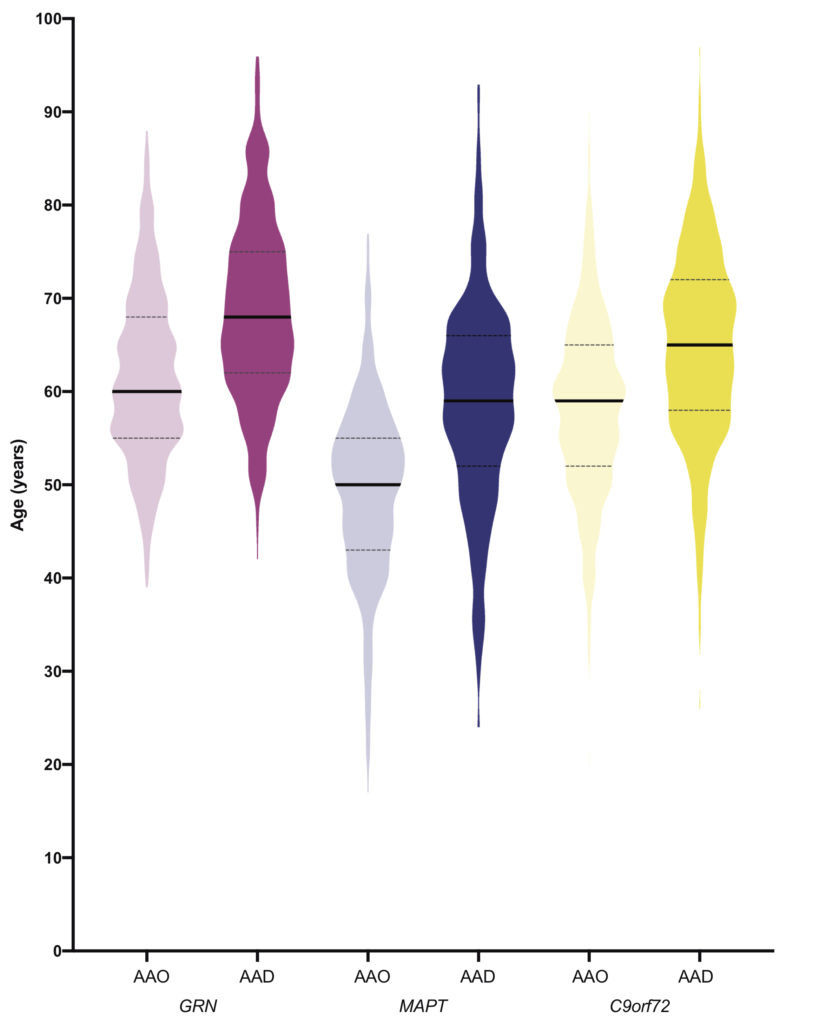

People often ask us what age they will develop symptoms if they carry a mutation in one of the genes that causes FTD. The picture below shows the ages at which people developed symptoms and the ages at which they died in the main genetic groups.

We can also look at that in a different way, by examining the number of people who have developed symptoms by a particular age:

Most people with MAPT mutations develop symptoms between 40 and 60, and most people with GRN mutations or C9orf72 expansions develop symptoms between 50 and 70. However for each group, there are people both younger and older than that.

All of the individual GRN mutations show a similar picture in the age of onset, but the individual MAPT mutations are different and some have a younger age at onset than others, as shown in the picture below.

Interestingly, for both the GRN and C9orf72 genetic groups there are a small number of people who live into their 80’s and 90’s and who only develop symptoms at this point, or who have yet to develop symptoms. This is a genetic phenomenon called age-related penetrance. We do not yet fully understand why this is the case.

Within an individual family there can be some variability in the age at which people symptoms. The least variability is in the MAPT group where people will commonly develop symptoms at a similar age to the average age of symptom onset in the family. There is more variability within the C9orf72 and GRN groups where there can sometimes be at least ten years between the age of symptom onset in two family members. We investigated this in the large international study we performed as part of the FTD Prevention Initiative (FPI): if 1 is a perfect correlation between the average age of symptom onset within the family and 0 is no correlation, for the MAPT group the number is 0.6, for the C9orf72 group 0.4, and for the GRN group 0.2.

Although studies have shown a slightly younger age at onset in more recent generations, we think this is related to better recognition of symptoms amongst other things, rather than the genetic phenomenon called anticipation.

We think that there is likely to be a mix of factors that can modify the age at which people develop symptoms. Some of these will be other genes and some may be ‘environmental’ factors. So far, research studies have identified a few genes that seem to affect the age at onset:

- TMEM106B: carrying the ‘risk’ variant of this gene seems to lead to a younger age at onset in people with GRN mutations.

- Changes in an area of the genetic code on chromosome 6 which contains two overlapping genes (LOC101929163 and C6orf10) has been shown to be associated with a younger age at onset in people with C9orf72 expansions.

It is not yet been clearly shown whether people with longer C9orf72 expansions have a younger age at onset, and more research is being performed in this.

The most common clinical presentation of all genetic forms is bvFTD. However, other FTD clinical syndromes can also be seen:

- PPA is less common than bvFTD in genetic FTD. However, nonfluent and mixed variants of PPA can be seen particularly in people with GRN mutations. PPA occurs to a lesser extent in people in the other genetic groups. although people with MAPT mutations often develop semantic problems after they have developed changes in behaviour.

- CBS is seen occasionally in people with genetic FTD, usually in people with GRN mutations, and sometimes in people with MAPT mutations.

- PSP is seen very occasionally in people with MAPT mutations.

- ALS and the overlap of bvFTD with ALS are seen commonly in people with C9orf72 expansions.

We sometimes see a very slowly progressive set of symptoms in people with C9orf72 expansions with mild changes in behaviour similar to those seen in autistic spectrum disorders. We also see a group of people with C9orf72 expansions who present with delusions and hallucinations similar to schizophrenia. Very rarely in the C9orf72 group, some people’s first symptoms are changes in their movements similar to those seen in Huntington’s disease.

The different syndromes that can present in the other genetic groups is less clear. However, recent studies have shown that mutations in the TBK1 gene can cause any of bvFTD, PPA, CBS, FTD-ALS, and ALS.